architecture: What we build. Don't Count Your Titanium Eggs Before They've HatchedWhy architects can't predict the future. By Witold Rybczynski

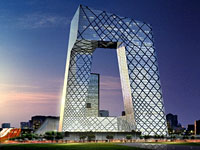

Abu Dhabi has recently announced plans to turn itself into a sort of Arabian Left Bank, with cultural venues designed by Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, and Jean Nouvel. Beijing, meanwhile, is completing the giant steel bird's nest of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron's Olympic Stadium, and also has Paul Andreu's titanium-egg National Theater, and Rem Koolhaas' unusual state television headquarters, which locals have dubbed "the twisted donut." An obscure sheikhdom on the Gulf and the world's largest Communist dictatorship have unexpectedly become the latest hotbeds of avant-garde architecture.

Avant-garde is a French term that originally meant the advance guard of an army, and in the late 1800s came to refer to pioneering painters, particularly the Impressionists, who considered themselves to be at the forefront of art. Since that time, the concept of an avant-garde has become popular in architecture, where "mainstream" has become a term of opprobrium, and anyone worth their salt is "experimental," "innovative," or "cutting edge." The clear implication is that buildings designed by avant-garde architects are ahead of their time. But are steel bird's nests, titanium eggs, and twisted helixes really a portent of the future?

In some ways, the term architectural avant-garde is an oxymoron, since an architect, unlike a painter, is able to experiment only within relatively narrow bounds. Buildings are expensive, and they are intended to last a long time, so the people who build them tend to be risk-averse. But even an architect who finds a patron—like the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, or the Chinese government—willing to take a chance, still faces the limitations of building regulations and existing construction materials and techniques. True experiments in building are few and far between. [for more click on the heading]

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home